US Sanctions on Myanmar Crypto Entities Targeting $10 Billion Scam Network

On September 8, 2025, the U.S. Treasury hit nine crypto-related entities in Myanmar with sweeping sanctions - not because they were mining Bitcoin or running decentralized exchanges, but because they were running forced-labor fraud factories. These weren’t shady startups. They were armed compounds in Shwe Kokko, a lawless zone on the Thai-Burmese border, where people were held captive and forced to scam Americans out of billions using fake crypto investments.

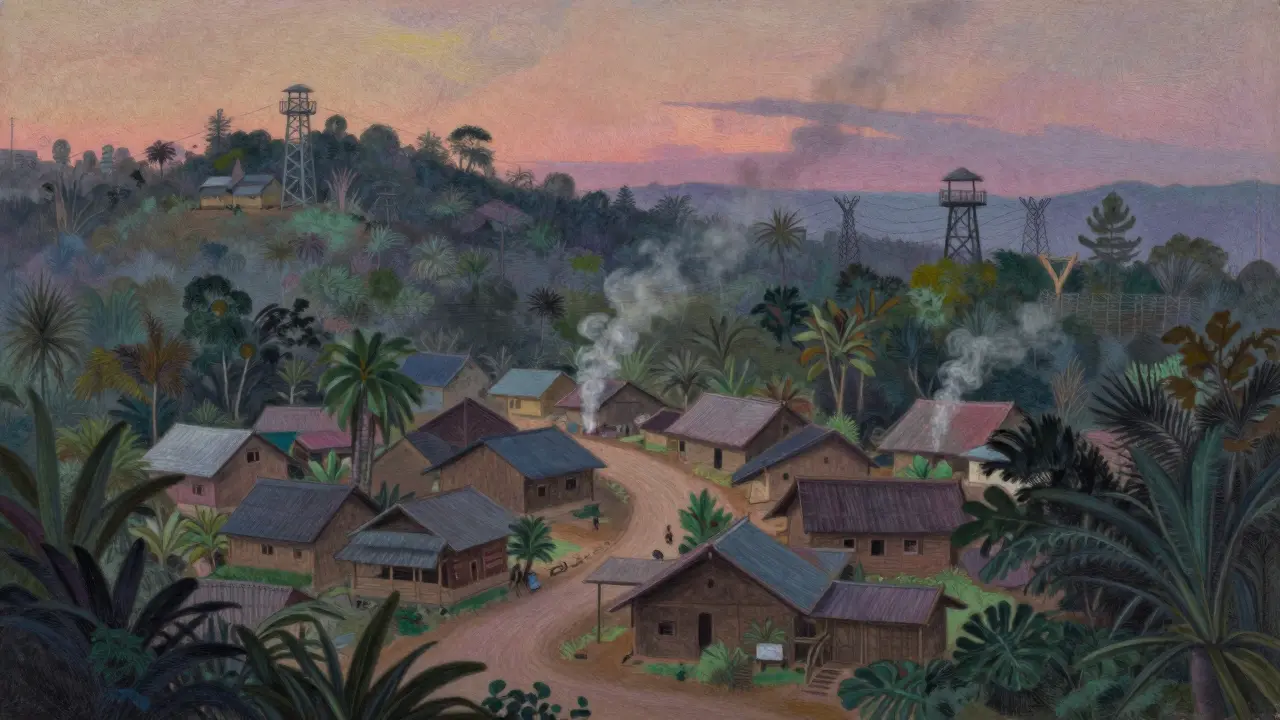

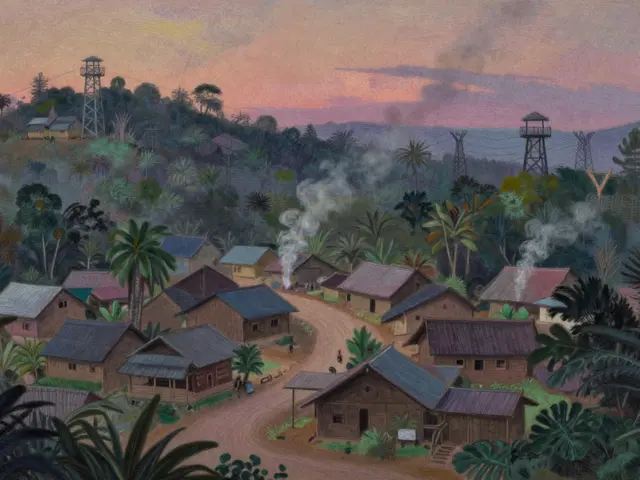

How a Tiny Town Became a Global Crypto Crime Hub

Shwe Kokko used to be a quiet border town. Now, it’s ground zero for one of the biggest financial crime operations in modern history. The area is controlled by the Karen National Army (KNA), a militia group that’s been protected by Myanmar’s military junta. In exchange for cash and weapons, the KNA lets cyber scam syndicates operate openly. Inside these compounds, victims - often lured with fake job offers from Malaysia or the Philippines - are locked in, beaten, and forced to run phishing campaigns 18 hours a day. These aren’t random scammers. They’re organized criminal networks with corporate-like structures. Teams handle social media outreach, fake websites, customer support (to keep victims hooked), and crypto laundering. The money flows through mixers, chain-hopping wallets, and shell companies in Cambodia before disappearing into the global financial system. The U.S. Treasury says Americans lost over $10 billion to these operations in 2024 alone - more than the GDP of 70 countries.What the Sanctions Actually Do

The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) didn’t just freeze bank accounts. They froze everything. The nine Myanmar-based entities named in the sanctions are now blocked from any U.S. financial system. That means:- No U.S. dollars can flow into or out of their wallets

- No American company can provide them with software, servers, or cloud services

- No U.S. citizen can trade with them - even accidentally

Why This Is Different From Past Actions

This isn’t the first time the U.S. has cracked down on crypto scams. But it’s the first time sanctions were applied under four separate executive orders at once:- E.O. 13851 - Targets transnational criminal organizations

- E.O. 13694 - Focuses on malicious cyber activity

- E.O. 13818 - Punishes human rights abuses

- E.O. 14014 - Addresses threats to Burma’s stability

Who’s Behind It: The Karen National Army and the Military Junta

The KNA isn’t some rogue militia. It’s a semi-official armed group with direct ties to Myanmar’s military. Its leader, Saw Chit Thu, and his two sons, Saw Htoo Eh Moo and Saw Chit Chit, were named in the sanctions. Their role? Providing security, bribing local officials, and collecting a cut of every dollar stolen. The military junta in Naypyidaw doesn’t publicly endorse these scams - but they don’t stop them either. In fact, they profit. The KNA pays a percentage of its earnings to the military in exchange for weapons, fuel, and protection from international pressure. The U.S. Treasury explicitly called this out: “The KNA has benefitted from its connection to Burma’s military in its criminal operations.” That’s a warning. Next, the military itself could be targeted.How These Scams Work - In Plain Terms

Here’s how it plays out for an American victim:- You get a DM on Instagram or Facebook: “Invest in this new crypto token. Guaranteed 200% returns in 30 days.”

- The site looks real - professional design, fake testimonials, live chat with “customer support.”

- You send ETH or USDT. The site shows your balance rising.

- You try to cash out. They say there’s a “verification fee.” You pay it.

- Then another fee. Then another.

- Eventually, the site vanishes. Your money is gone.

What This Means for Crypto Users

If you’re trading crypto, this matters. Why? Because these scams are changing how regulators see the whole industry.- Exchanges are under more pressure to block wallets linked to sanctioned entities. Some are already freezing addresses flagged by OFAC.

- Wallets that have ever interacted with a sanctioned address may get flagged - even if you didn’t know.

- Regulators are pushing for real-time transaction monitoring. Expect more KYC checks and longer withdrawal delays.

What’s Next? The Domino Effect

The September 2025 sanctions were just the start. Treasury officials said this was part of “a series of actions taken in the last several months.” That means more are coming. Expect:- Sanctions on Cambodian crypto exchanges that laundered funds

- Pressure on Thai banks that processed payments for Shwe Kokko compounds

- More designations against individuals - not just companies

- Collaboration with Interpol and ASEAN to shut down physical scam centers

How to Protect Yourself

You can’t stop a scammer in Myanmar. But you can stop yourself from becoming a victim:- Never invest based on a DM or random YouTube ad

- Check if a project is listed on reputable exchanges (Coinbase, Kraken, Binance - not obscure ones)

- Use blockchain explorers to trace wallet history. If a wallet has ever interacted with a sanctioned address, avoid it

- If it sounds too good to be true - it is. No one gives 200% returns. Ever.

Why This Matters Beyond Crypto

This isn’t just a crypto story. It’s a story about power, corruption, and how technology can be weaponized against the vulnerable. The same tools that let you send money across borders in seconds are now being used to enslave people and steal life savings. The U.S. sanctions are a turning point. For the first time, the world is treating crypto scams not as technical fraud - but as organized crime with blood on its hands. And that changes everything.Are U.S. citizens at risk of being sanctioned for accidentally using a crypto wallet linked to Myanmar?

No. OFAC sanctions target specific entities and individuals - not ordinary users. If you accidentally sent crypto to a sanctioned address, you won’t be punished. But your transaction will be flagged, and your exchange may freeze your account temporarily while they investigate. The key is not to knowingly interact with blocked addresses. Always check wallet history using blockchain explorers like Etherscan or Solana Explorer before sending funds.

Can I still trade crypto with exchanges based in Southeast Asia?

Technically yes - but it’s risky. Many exchanges in Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar are now under U.S. scrutiny. Even if they’re not directly sanctioned, their banking partners may be cut off. This can lead to sudden withdrawals freezes or account closures. If you use an exchange that’s not based in a regulated jurisdiction like the U.S., EU, or Australia, you’re taking on more risk. Stick to platforms with clear compliance teams and public licensing.

What happened to the people trapped in the Shwe Kokko scam compounds?

The U.S. government doesn’t have direct access to these compounds, so rescue operations are handled by international NGOs and regional partners like Thailand’s border police. Some victims have been freed in raids, but many remain captive. The sanctions are meant to cut off funding so these operations collapse - making it harder for traffickers to hold people hostage. Rescue efforts are slow and dangerous, but pressure from sanctions increases the chances of future raids.

Is cryptocurrency itself to blame for these scams?

No. Cryptocurrency is a tool - like cash or wire transfers. The problem isn’t blockchain technology. It’s the lack of regulation in certain regions, combined with corruption and weak law enforcement. Scammers use crypto because it’s fast, borderless, and harder to trace - but they could just as easily use prepaid cards or shell companies. The solution isn’t to ban crypto. It’s to regulate the bad actors and hold exchanges accountable for monitoring suspicious flows.

Will these sanctions stop the scams for good?

Not overnight. These networks are adaptable. If Shwe Kokko gets too hot, they’ll move to another town - maybe in Laos or the Philippines. But the sanctions are designed to make it harder, costlier, and riskier to operate. With every target added, the network shrinks. The goal isn’t to wipe them out in one move - it’s to strangle them over time. This is a long-term campaign, and the U.S. is showing it’s in for the long haul.

this is wild i just sent some crypto to a sketchy site last month and now i’m terrified

I can't believe we're still letting this happen... these people are being tortured for profit and we're just talking about wallet addresses? Come on. This is modern slavery with a blockchain twist. We need boots on the ground, not just sanctions.

I’ve been watching this for years... the way these scams are structured is chilling. They’re not just phishing-they’re psychological warfare. Victims are manipulated into sending more money because they’re told they’re ‘close’ to cashing out. And the people doing the scamming? Often trapped too. It’s a horror show with a corporate logo.

so the u.s. finally got around to caring about human suffering... when it involves crypto? classic. 😒

i hope this helps the victims... i cant imagine being forced to scam people just to survive

the fact that we treat this as a financial crime instead of a humanitarian emergency says everything about where our priorities lie

if you’re using an exchange that doesn’t do proper KYC or has no public compliance team, you’re already part of the problem. Check their website. Do they even have a legal disclaimer? If not, move your funds. Now.

you know what’s really sad? The people who built these scam factories were probably once hopeful. Maybe they believed in blockchain. Maybe they thought they could change the world. Now they’re chained to a desk in a compound, injecting themselves with speed just to hit their quota. And the real criminals? They’re sipping whiskey in Naypyidaw while the U.S. freezes wallets. It’s not capitalism. It’s capitalism with a death sentence.

this is the kind of thing that makes me proud to be part of a community that actually gives a damn. We’re not just trading tokens-we’re fighting for people. These sanctions? They’re not just legal moves. They’re moral ones. And if you think crypto is just about money, you’re missing the whole damn point.

The U.S. Treasury’s multi-executive-order approach is unprecedented. It signals a paradigm shift: crypto crime is no longer a technical violation-it is a violation of human dignity. This is the first time the full weight of federal law has been applied to digital-age slavery. History will note this as the moment the world stopped treating fraud as a victimless crime.

oh wow another crypto crackdown. what a surprise. next they’ll ban cash because drug dealers use it too. this is just a power grab disguised as justice

this is all part of the globalist agenda to control our money. the u.s. doesn’t care about victims-they care about control. next they’ll track every transaction through your phone. wake up people

oh look, the government finally noticed that criminals use technology. who knew? maybe next they’ll ban knives because someone stabbed a guy. brilliant strategy, guys.

they’re calling it modern slavery? cool. now let’s call the whole damn system slavery. You think these people in Shwe Kokko are the only ones suffering? The guy in Ohio working 80 hours a week to pay off his student loans? The single mom in Texas choosing between rent and insulin? This isn’t justice-it’s theater. The real criminals are the ones who built the system that lets this happen.

The application of four distinct executive orders simultaneously represents a landmark legal convergence: transnational criminality, cyber malfeasance, human rights violations, and geopolitical destabilization are now being treated as interdependent phenomena. This is not merely enforcement-it is jurisprudential evolution.

stop talking. act. rescue the people. shut down the compounds. freeze the money. no more words.

you all think this is about justice? nah. this is about the u.s. wanting to control the global crypto market. they don’t care about the victims-they care about dominance

I just watched a video of a guy in Shwe Kokko being dragged out by Thai police... he was smiling. He was smiling. After all that. That’s not hope. That’s trauma. And we’re just sitting here debating sanctions? We’re the ones who let this happen. We’re the ones who clicked on those ads. We’re the ones who sent the money. We’re the reason they’re still there.

i mean, sure, the scams are bad... but didn’t these people know crypto was risky? like, if you’re gonna trust some random instagram influencer with your life savings... you kinda signed up for this, right? just saying

they’re calling it slavery? lol. the real slaves are the ones working at Coinbase for minimum wage while these scammers make millions. at least the people in shwe kokko are getting fed.

you think the u.s. cares about the victims? they care about the money. they want to stop the flow so they can take it. this is about control, not compassion.

The structure of these operations mirrors corporate supply chains. The victims are labor. The tech is infrastructure. The crypto is currency. The military is the board of directors. The U.S. sanctions are a strike against the supply chain-not just the product. This is the first time the entire ecosystem has been mapped and targeted. It’s not just about stopping crime. It’s about dismantling a new kind of state.