Bangladesh's Foreign Exchange Act and Its Impact on Cryptocurrency

Bangladesh Crypto Policy Explorer

Bangladesh has implemented a comprehensive prohibition on cryptocurrency activities under the Foreign Exchange Regulations Act (FERA) of 1947.

While the Bangladesh Bank has issued a blanket ban on crypto use, transactions still occur through informal networks and mobile apps.

- Foreign Exchange Regulations Act (FERA) of 1947: Defines "currency" but lacks formal declaration for digital tokens

- Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA): Relies on FERA definitions; enforcement is uncertain

- Income Tax Ordinance of 1984: Treats crypto as property for tax purposes

Bangladesh Bank enforces the ban primarily through:

- Monitoring USD-denominated transactions for crypto-related patterns

- Flagging transfers to known exchange accounts

- Requiring local agents to facilitate peer-to-peer swaps

Despite these measures, tech-savvy users access global platforms via mobile apps.

The National Board of Revenue (NBR) treats cryptocurrency gains as property, subjecting them to capital gains tax.

As of 2025, no specific crypto tax framework exists, but NBR plans to issue guidelines.

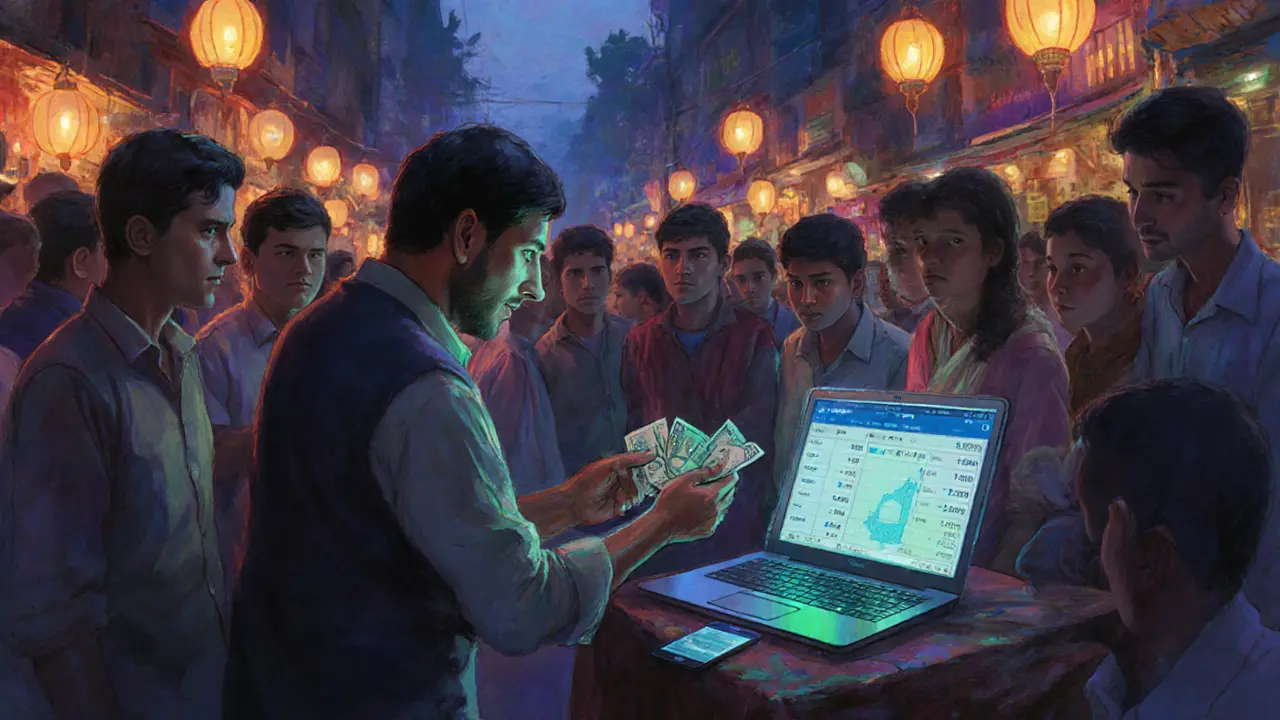

An active informal economy thrives in Bangladesh:

- Mobile apps for major exchanges remain available

- Agents in Dhaka and Chittagong exchange Taka for Bitcoin

- Peer-to-peer platforms operate with minimal oversight

Estimates suggest hidden crypto volumes may rival Pakistan's reported $25 billion informal market.

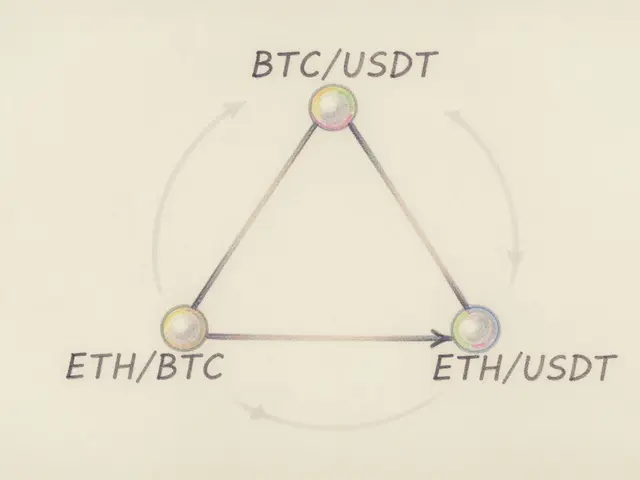

Compare Bangladesh's stance with neighboring countries:

| Country | Regulatory Stance | Tax Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | Comprehensive prohibition | Capital gains tax (varies by income slab) |

| Pakistan | Regulated framework | 15% flat rate |

| India | Regulated with high taxation | 30% + 1% TDS |

Experts suggest potential reforms:

- Amending FERA to define digital tokens explicitly

- Creating a dedicated crypto regulator

- Establishing clear tax guidelines

Until legislative changes occur, the current environment remains a mix of strict enforcement, vague tax obligations, and a resilient underground market.

Summary

Bangladesh's approach to cryptocurrency is defined by a legal gray area created by outdated laws and inconsistent enforcement. While the state bans crypto, it simultaneously taxes profits from these activities, leading to a paradoxical situation. The country's neighbors are moving toward regulation, potentially placing Bangladesh at a regional disadvantage.

Quick Takeaways

- The 1947 Foreign Exchange Regulations Act (FERA) is the legal backbone behind Bangladesh's crypto ban.

- Bangladesh Bank has not formally declared digital tokens as "currency," leaving a gray area in criminal enforceability.

- All crypto gains are treated as property under the Income Tax Ordinance, meaning taxes apply to technically prohibited activities.

- Despite the ban, a sizable underground market thrives via mobile apps and local agents.

- Neighboring countries are moving toward regulation, putting Bangladesh at a regional disadvantage.

Legal Foundations: The Foreign Exchange Regulations Act (FERA) of 1947

When you hear about Bangladesh's crypto crackdown, the first law that comes up is the Foreign Exchange Regulations Act (FERA) of 1947. Section2(b) of FERA defines “currency” in two buckets: (i) traditional instruments like notes, cheques, drafts, etc., and (ii) any instrument the Bangladesh Bank may declare as currency through a Gazette notification. Because the central bank has never issued such a notification for Bitcoin or other digital tokens, the statutory basis for calling crypto “currency” is shaky.

Legal scholars point out that without a formal Gazette declaration, prosecutions under FERA for crypto‑related offenses are on uncertain ground. The same definitional gap ripples into the Anti‑Money Laundering Act (AMLA), which leans on FERA’s definition of foreign exchange.

Bangladesh Bank’s Practical Ban

The country's central bank, Bangladesh Bank, issued a blanket prohibition in 2017. The warning covers any use, trade, or possession of crypto assets, citing money‑laundering and terrorism‑financing risks. While the ban is clear, its enforcement leans heavily on the banking system:

- Banks monitor USD‑denominated credit and debit card transactions for crypto‑related patterns.

- Financial institutions flag transfers to known exchange accounts, even if the accounts are overseas.

- Local “agents” facilitate peer‑to‑peer swaps of Bangladeshi Taka for crypto, keeping a low profile to avoid direct bank involvement.

These measures create a de‑facto barrier, but they don’t stop tech‑savvy users from accessing platforms like Binance or KuCoin via the Google Play Store.

Tax Implications via the National Board of Revenue (NBR)

Even though crypto activities are prohibited, the National Board of Revenue (NBR) treats crypto as property for tax purposes. Under the Income Tax Ordinance of 1984, any profit from selling or exchanging digital tokens is subject to capital‑gains tax. In practice, this creates a paradox: you could be taxed on earnings from an activity the state officially bans.

As of 2025, no dedicated crypto tax framework exists, but the NBR has hinted at future guidelines that would clarify reporting requirements and rates.

Ground Realities: The Underground Crypto Market

Despite the official stance, a vibrant underground ecosystem thrives:

- Mobile apps for major exchanges remain downloadable on standard app stores.

- Informal agents in Dhaka and Chittagong exchange Taka for Bitcoin, usually for a small commission.

- Peer‑to‑peer platforms like LocalBitcoins operate with minimal oversight.

Because transactions bypass formal banking channels, accurate market data is scarce. Regional estimates suggest that Bangladesh’s hidden crypto volume could rival Pakistan’s reported $25billion informal market.

Regional Comparison: How Neighbors Are Handling Crypto

| Country | Regulatory Stance | Key Legislation | Tax Rate on Gains | Notable Authority |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | Comprehensive prohibition | Foreign Exchange Regulations Act (1947); AMLA | Capital gains tax (rate varies by income slab) | Bangladesh Bank, NBR |

| Pakistan | Regulated framework | Pakistan Digital Assets Authority Act (2025) | 15% flat on crypto profits | Pakistan Digital Assets Authority (PDAA) |

| India | Regulated with high taxation | Income Tax Act, Crypto‑Tax Rules (2023‑2025) | 30% on gains + 1% TDS | Reserve Bank of India, Finance Ministry |

Ongoing Debate and Future Outlook

Academics like Dr. BMMainul Hossain argue that an outright ban is ineffective and suggest a regulated approach. Their view reflects a growing sentiment that Bangladesh risks missing out on digital‑asset innovation if it stays isolated.

Potential paths forward include:

- Amending FERA to expressly define digital tokens as a separate asset class.

- Creating a dedicated crypto regulator, similar to Pakistan’s PDAA.

- Launching a clear tax guideline that reconciles the paradox of taxing illegal activity.

Until legislation catches up, the current landscape will continue to be a mix of strict banking directives, vague tax obligations, and a resilient underground market.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is owning Bitcoin illegal in Bangladesh?

The Bangladesh Bank has issued a ban on possession, trading, and use of Bitcoin. While the law leans on the Foreign Exchange Regulations Act, the lack of a formal Gazette declaration creates a legal gray area. Practically, authorities treat it as prohibited.

Do I have to pay tax on crypto profits?

Yes. The National Board of Revenue treats cryptocurrencies as property, so capital‑gains tax applies to any profit, even though the activity itself is banned.

Can I use a foreign exchange platform to buy crypto?

Bank transfers to overseas exchanges are closely monitored and often flagged. Many users resort to peer‑to‑peer agents or mobile apps that bypass traditional banking channels.

What are the penalties for violating the crypto ban?

Violations can lead to criminal prosecution under the Foreign Exchange Regulations Act, with penalties ranging from fines to imprisonment, though actual enforcement varies due to the definitional gaps.

Will Bangladesh change its stance on crypto soon?

The government has signaled intent to review the regulatory framework, but no concrete timeline exists. Experts expect either a clearer prohibition or a shift toward regulated adoption within the next few years.

Reading through the Bangladeshi crypto clampdown feels like watching a tug‑of‑war between old‑school finance and the relentless surge of digital assets. The fact that they still cling to a 1947 law shows just how out‑of‑date the regulatory mindset is. Yet the enforcement tactics – monitoring USD flows and flagging exchange accounts – expose a sophisticated, if clumsy, approach. It’s almost poetic that the underground market thrives exactly because the official stance is so heavy‑handed. In the end, the ban may just be a costly echo of nostalgia rather than a functional policy.

Bangladesh’s outright ban is a textbook case of fear‑driven policymaking. They slap a prohibition on crypto but then slap taxes on the same activity, which is pure contradictory nonsense. If they wanted to control capital flows, they should modernize the law instead of playing Catch‑22 with their citizens.

The narrative surrounding Bangladesh’s crypto stance is riddled with paradoxes that merit a deeper unpacking. First, the reliance on the Foreign Exchange Regulations Act of 1947 demonstrates a legislative lag that fails to recognize digital tokens as a distinct asset class, leaving enforcement on shaky ground. Second, the Bangladesh Bank’s prohibition, while clear on paper, relies heavily on monitoring traditional banking channels, which savvy users can easily bypass through mobile apps and peer‑to‑peer networks. Third, the National Board of Revenue treats crypto gains as property, imposing capital‑gains tax on an activity that the state simultaneously deems illegal, creating a legal quagmire for any taxpayer who dares to comply.

Moreover, the underground market’s resilience highlights an economic reality: when demand persists, supply will find a way, no matter how stringent the official narrative. Agents in Dhaka and Chittagong act as de‑facto custodians, facilitating swaps that skirt the formal banking system, thereby eroding the intended efficacy of the ban. In addition, the lack of a dedicated crypto regulator means that policy enforcement is fragmented across multiple agencies, each interpreting the outdated statutes through their own lens.

Regionally, Bangladesh’s isolationist posture puts it at a competitive disadvantage. Pakistan’s recent Digital Assets Authority Act provides a regulated framework that encourages innovation while maintaining oversight, and India’s high‑tax regime, though strict, offers clear guidelines that attract institutional participation. Bangladesh’s refusal to define digital tokens in law not only hinders domestic fintech growth but also discourages foreign investment, as the uncertainty surrounding compliance becomes a barrier to entry.

Looking ahead, the most viable path involves amending FERA to explicitly recognize digital tokens, establishing a dedicated crypto regulator, and publishing concrete tax guidance. Such reforms would resolve the current paradox of taxing illegal activity and enable Bangladesh to harness the economic benefits of blockchain technology. Until then, the country remains locked in a tug‑of‑war between enforcement and evasion, with its citizens caught in the crossfire of an outdated legal framework.

The ban is just a nostalgic checkpoint, not a real solution.

Honestly, the whole thing feels like trying to stop a river with a sieve. People will always find a way to move value.

While the official rhetoric paints crypto as a terrorist‑funding nightmare, the reality on the ground is far more nuanced. In Dhaka’s informal circles, exchanges happen daily, and the community has built a sense of trust around local agents. This organic network operates under the radar, effectively sidestepping the heavy‑handed banking monitoring that the central bank employs. It’s a classic example of regulatory arbitrage: the law says no, but the market creates its own rules. If Bangladesh wants to truly protect its financial system, it should consider integrating these informal players into a regulated framework rather than driving them further underground.

Bangladesh’s situation shows how a blanket ban can backfire. Instead of stifling crypto, it fuels a shadow ecosystem that’s harder to monitor. A balanced regulatory approach could bring transparency while still addressing AML concerns. 🌐💡

From a compliance standpoint, the absence of a gazette notification on digital tokens creates a legal vacuum that regulators exploit. This ambiguity lets banks claim they’re enforcing FERA, yet the underlying statutes weren’t designed for decentralized assets, making any prosecution a stretch at best.

Respectfully, the energy in the Bangladeshi crypto community is impressive. They’re adapting fast, using mobile apps and peer‑to‑peer platforms even under pressure. This shows that innovation thrives when there’s demand, regardless of regulatory roadblocks.

Let’s stay optimistic: the pressure from regional peers might push Bangladesh toward a smarter policy. If they can strike a balance, they’ll unlock a wave of fintech talent that’s already buzzing under the surface.

The underground market isn’t just about evasion; it’s a sign of unmet financial needs. Providing a clear, tax‑friendly framework could turn this hidden activity into a legitimate sector that contributes to the economy.

It is evident that the current prohibition is anachronistic and detrimental to Bangladesh’s competitive standing.

Yo, the ban feels like trying to lock a door with a paperclip. People find a way, and the market just keeps rolling.

From a cultural lens, Bangladesh’s hesitation mirrors a broader tension between tradition and digital disruption. Embracing a regulated path could bridge that gap and showcase the country’s innovative spirit.

The current FERA‑centric approach is like using a horse‑and‑buging to drive a Tesla. 🚗💨 Without a modern framework, you’ll just stall on the highway of global finance. 🛑

Honestly, it’s another case of regulators trying to police something they don’t fully understand and ending up with a half‑baked policy.

From an ethical standpoint, criminalizing a technology while taxing its profits is a contradictory stance that undermines the rule of law and erodes public trust in institutions.

Let’s cut to the chase: Bangladesh needs to stop the mixed messages, define crypto clearly in law, and give innovators a fair playing field. Anything less just fuels the shadow market.